The Answer is Still No.

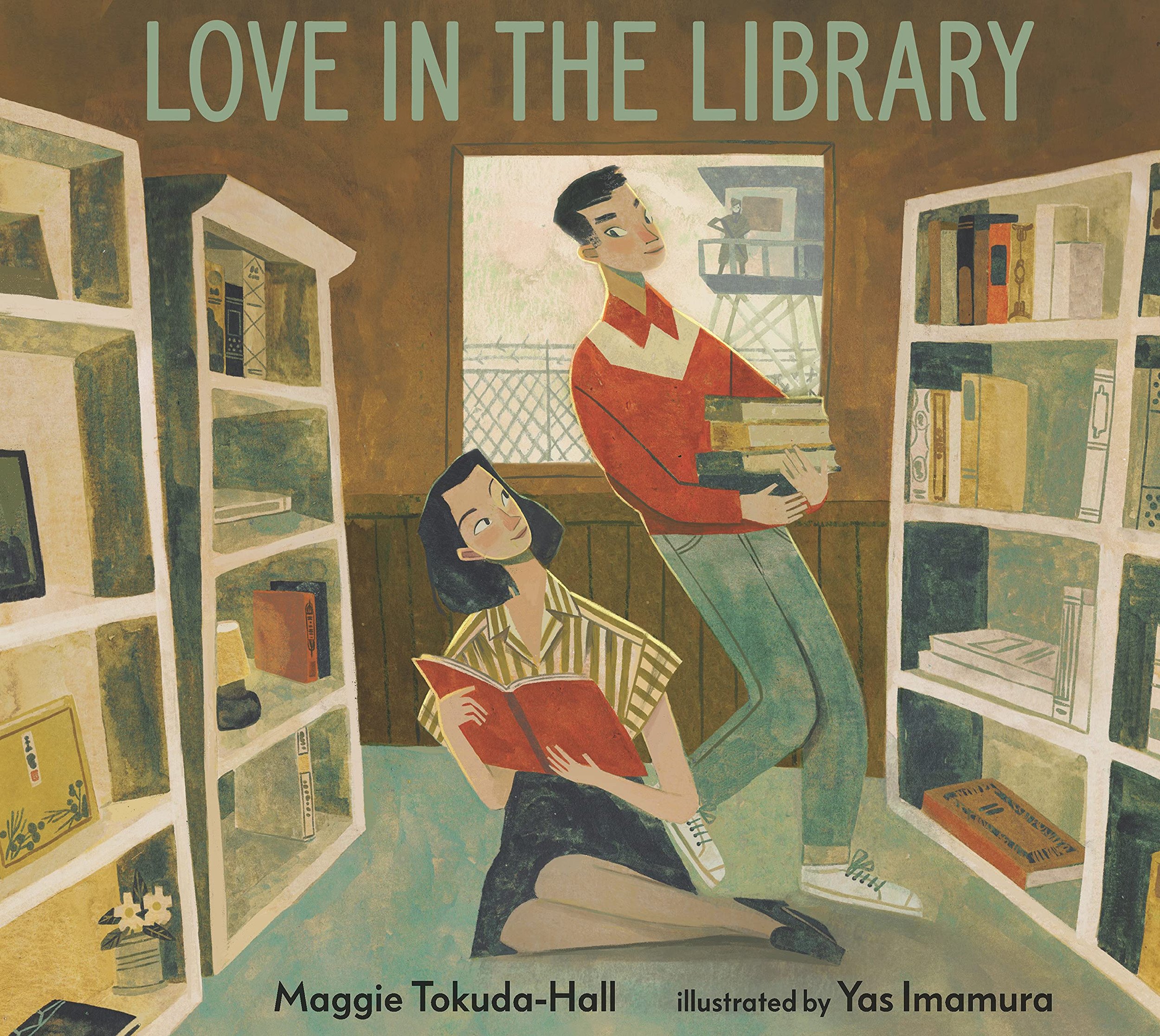

I would prefer, in all of this, to just take the licensing deal. I would like that better than solidarity, or kind messages of support, or retweets, or that flurry of sales that accompanied my initial blog post about what had happened. I still want that distribution, that reach that only Scholastic can provide. I want Love in the Library to be in schools, where teachers can expertly contextualize it.

But the price remains too high.

I appreciate that Scholastic was swift in their apology, even if it took a couple tries to smooth the language into something more thorough. I appreciate that they made those apologies public. I appreciate that they amended their offer such that they would license my book with my author’s note intact. I appreciate, most of all, the current employees of Scholastic who reached out to me directly with apologies and horror. I am aware that it is an enormous corporation with so many people who did not deserve to have their essential work dragged through the mud because of a decision made by a different wing of the company. I appreciate that capitalism is cruel, and that is no single corporation’s fault.

I have tried to approach this situation from the perspective of restorative justice, rather than that of revenge or punishment or shame. Nothing is gained, in my opinion, by screaming at someone until they offer a symbolic apology, if nothing changes. I was not only concerned that they made right by me, but that they made right for my community, which is the community of marginalized authors. I had hoped Scholastic would make amends in such a way that would demonstrate a better understanding of the problem, and change their behavior.

But from what I’ve seen, nothing meaningful has changed. And I remain skeptical that anything will.

I had a meeting a week after I went public with, among other people, Peter Warwick, the CEO of Scholastic, and Rose Else-Mitchell, the president of the Education Solutions in Scholastic. In it, I had hoped for three things. One, an honest and transparent recounting of what had happened, not just to me but also in regards to the accusation I had heard from Sayantani DasGupta, a mentor for the Rising Voices program who accused Scholastic of hesitancy to include any LGTBQ+ material in the collection. Two, evidence of durable process change to their curation process. And lastly, I wanted to hear what their plans were to combat the rising, fascist culture of book bans. The last to me was, in many ways, the most important. The edit had been asked of me to try and accommodate that same culture. If they truly meant the words of their credo, which had been quoted in nearly all their apologies to me, then surely they would have a plan.

But not a single one of these needs were met.

To the first concern, no one in the meeting was prepared to speak about what had happened. The editor who had made the decision was not in the room, and no one was willing to speak to it in their absence. I personally, if confronted with the same decision, would have prepared at least one person to answer the very basic question of what happened. Instead, I was told it was a mistake, someone simply having a bad day at work, which is either an obfuscation or a lie. It was a weighted decision, one made to mind their sales priorities while also trying to heed the curation of the AANHPI mentors they had enlisted for this collection. I know this because justification for the edit was provided to my subrights representative from Candlewick. They did not slip and fall into censorship. They asked for it directly. Whether that decision was made because the single editor who was not present thought my language was too strong, or if it was in response to a company culture of maintaining a rigid centrism I do not know and cannot say. Additionally, no one would even acknowledge the accusation of limiting LGBTQ+ inclusion in the collection, despite another mentor who was on the call chiming in that they too had witnessed it.

To my second concern, I was told that an external auditor would be enlisted to see what had happened. Of all my concerns, this is the only one in which I saw even the potential for incremental progress. I look forward to the results of their audits. But from what they told me at the meeting, the goals were small in focus, and did not necessarily mean it wouldn’t happen again. I worried as I listened to their plan that it may simply mean that they would get better at not leaving an obvious paper trail as they did with me, or that worse, they would simply not include any books like mine– in which a marginalized person speaks frankly– at all in the future, rather than request an edit.

To my third, and most essential concern, the answers were the most disappointing. Firstly, they told me they provide annotations to teachers and librarians who are fighting bans. This, to my understanding from the meeting, simply means giving them the good reviews and marketing language for the books. This kind of information is available, for free, on my website. Or on Amazon under book description. Secondly, they told me that one of the members of Scholastic who was on the call– and here I am in the wrong for forgetting their name and what their role is– serves on a task force with PEN America that is concerned with fighting book bans. I do not mean to diminish her good work with a good group, but the efforts of a single staff member of a billion dollar corporation is not impressive. And lastly, they told me they combat that culture with their curation. Given that we were on the call due to a curatorial problem this was, perhaps, the most disappointing aspect of their answer. Annotations are not lawyers. The time of a single employee is not an investment. And their curation efforts are clearly problematic. Scholastic is a billion dollar company with a unique reach and impact in the education market. Their directive as purveyors of truth and literacy must be held to a higher standard than other publishers because of that unique position and privilege. They simply must do better.

And so I told them on the call that my answer was no. I would not license Love in the Library with them. They had not earned my trust. But I told them that I hoped they kept us all posted about what they did going forward. That I hoped they would be transparent and honest. Because if real change IS made? Then that deserves to be celebrated.

There is a metaphor I use when I present Love in the Library in schools, and it’s this: Imagine a bully. And one day, they punch you. Later they apologize to you. They say they shouldn’t have done that, that it wasn’t fair. But then the next day you see them punch someone else. And then the next day they kick someone. Each of these incidents are separate, sure, in that whatever the perceived slight on the Bully’s part was may vary. But they are also the same in that the Bully has been cruel to each of you. Would you accept that apology? Would you believe that the Bully meant it if they persist in their behavior?

In my presentation I am referring to the US government. But I think it can be used in this situation, too. The apology is a good start. It cannot be accepted until real changes are made.

Do I believe those changes will be made? No. But I’d sure love to be wrong.

Thank you to all who have offered your solidarity and support. For those who have asked, the book is available in its complete form wherever books are sold. If you would like a signed copy, please order through Mrs. Dalloway’s Books in Berkeley. Personalizations are available by request.