I was honored to be asked to give the keynote address at the Minidoka Pilgrimage this year. Over 200 descendants and survivors come from all over the country to visit and discuss what the incarceration means to us. The keynote is meant to set the tone for the weekend. This is that speech.

I’d like to thank my mother, who is here with me today. It was not until I became a parent that I understood the gravity and magnitude of the task of raising a child with honesty. I see now that it is a daily discipline, a source of exhaustion, and a monumental undertaking. I took it for granted as a kid because my mom just… told the truth. Even when the truth was devastating. I know now how tempting it is, to shield our babies from anything that could hurt them. I know now how deeply a parent loves their children, that we would do anything to keep them safe from hurt and strife and fear. But her discipline has imbued in me the bedrock belief that we all deserve the truth. That honesty is integral to any education worth having. And that the courage to wield the truth with compassion and clarity is perhaps my own highest calling. Thank you, Mom.

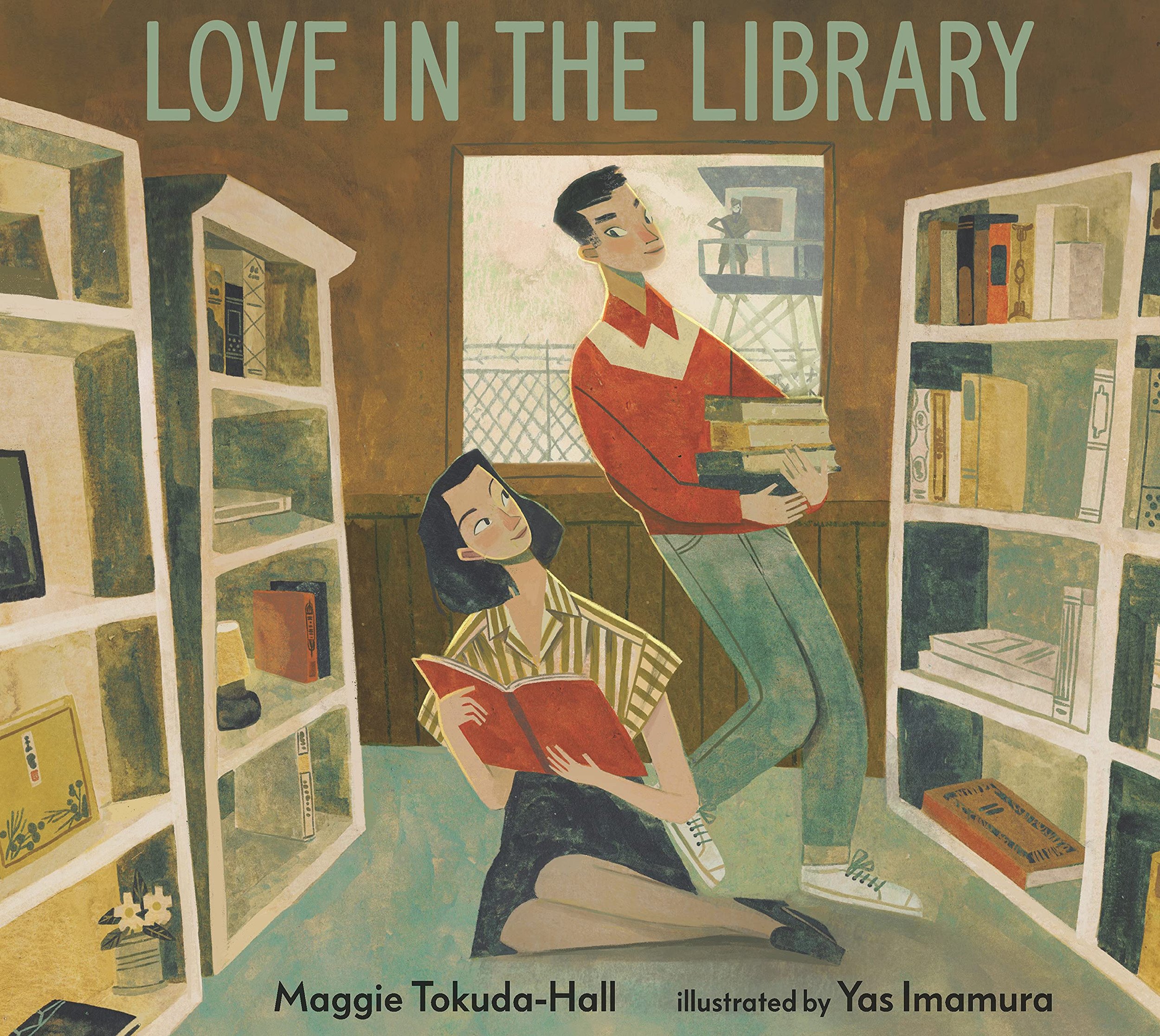

It is thanks to her hard line on truth that I wrote my book, Love in the Library, which takes place in Minidoka. Of all my work, that book has had the most impact on my life, as an author and as an activist. It is the true story of how my mother’s parents met in Minidoka.

Tama was a writer herself, and a talented one. But the racism toward Japanese Americans was such that she was never able to secure a publishing deal. That is why it was essential to me to end the book with her words: “The miracle is in us, as long as we believe in beauty, in change, in hope.” With the privilege and good fortune I now exercise, her words have, at long last, seen print in a book. And that makes me so proud.

I was honored to come to Minidoka, as a guest of Friends of Minidoka and the Idaho Librarian Association in early October of last year. In the airport, on the flight home, news came out of Israel of a horrendous attack. And even then I knew what would follow would only yield new horrors. I knew it as a Jew. And I knew it as a descendent of Minidoka survivors; that the single most perilous time for all nations comes in the wake of shocking violence.

The assassination of a German politician by a Jewish student was the justification for Kristallnacht, the first night that portended all the violence that was to come. The attack on Pearl Harbor, which saw our families put into a prison camp, still commemorated with little mention of the follow on acts of violence our government committed against its own people. We saw it in my own lifetime, after the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11th, which gave way to endless, ruinous wars all across the middle east, not to mention the establishment of a mass surveillance state that we still live under.

I scrolled my phone on October 7th as the death count swelled. As Israeli flags were posted across many of my own family member’s accounts. And I braced myself for the violence that was to come. But nothing could have prepared me for what we’ve seen.

When I wrote Love in the Library, I did not start with a mention of Pearl Harbor. I made this choice on purpose. Leading with the state line of justification for the deep injustice that followed is a mistake with several insidious repercussions. To start, a justification for the unjustifiable will always minimize the cruelty, absurdity, and violence of the reaction. It will also minimize the pain of survivors — sure you were uncomfortable, but what was the US supposed to do, not defend itself? — and treat their lives as acceptable collateral damage.

It will also occlude the climate of injustice and racism that preceded it. As if Japanese Americans had been whole-heartedly embraced by the American community until our ancestral nation attacked the Pearl Harbor; as if Palestinians had been treated equitably and justly by the Israeli government until the attack on October 7th; as if Jews posed a unique threat to the German people, and were hell bent on destroying that nation through crooked dealings and manipulation.

These lies can only survive in a climate in which the truth is suppressed.

It is no coincidence that in all three of these cultures— pre-WWII Germany, WWII America and contemporary Israel— stories that may beg to differ were and are violently suppressed. Japanese Americans who fought against incarceration were imprisoned, their voices subsequently erased from our history books. Even as a Japanese American I was not taught about the No-No boys until my adulthood. Nazi Germany simply burned the books that would threaten their Führer’s vision for the future. And in Israel, peace protestors are increasingly intimidated, fired from their jobs, and arrested for speaking out. In the United States, protestors with the same goal of peace are slandered as antisemites, even when thousands of us are Jews ourselves.

Injustice thrives in disinformation.

Disinformation is, of course, the defining characteristic of our time. From a convicted felon who dubbed all bad press about him as Fake News. To the rising culture of book bans that have swept our nation, and particularly in this state, in Idaho, where hb 710 has made libraries all financially liable for any complaint ANYONE makes about ANY book they find there for being “inappropriate.”

With Project 2025 looming over our nation on the fascist candidate’s ticket, we could see the dissolution of the Department of Education, which will only accelerate the dissemination of disinformation and the exclusion truth. Already books about Japanese incarceration are banned— my own book included. If we lose this upcoming election, it is not a stretch to believe that telling our stories at all could become illegal. This is by design— Project 2025 seeks to harden hegemony and hegemony requires the erasure of stories like ours.

In the United States, the fight against book bans has changed dramatically since Banned Books Week was started by the American Library Association in 1982. Book bans have always ebbed and flowed along with moral panics in the United States. But gone are the comparatively quaint days of banning Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark for being too, you guessed it, scary.

Now, bans don’t just seek to pull purportedly “offensive” content from the shelves. It’s to defund the shelves they sit on, in any institution of public learning that is funded enough to have shelves. The dark money, far-right extremists that favor bans have learned to capitalize on easily inflamed bigotries against LGBTQ+ and BIPOC creators who have only just been allowed entrance to the literary world. But, perhaps most infuriatingly of all, this has been accomplished through a contagious and pernicious lie: that there is pornography in the kids’ section. And that teachers and librarians are pedophiles, bent on grooming our children for sexual abuse.

A horrifying prospect! If it were true.

It’s not. But that doesn’t seem to matter. That these are life-ruining accusations has not slowed down anyone bent on banning books. Nationwide our fellow citizens spring up, deputized by their fear and resentment, and lob these bombs onto educators just doing their jobs. It’s a neat bit of psychological warfare. Because as soon as you have to say: “I’m not a pedophile!” you sound, unfortunately, just like a pedophile. And so institutions scramble to respond, wasting massive amounts of time and energy in institutions already short on funding and staff, fear spreads, and whole communities of educators are brought to heel and quietly start to censor themselves.

The argument is of course that they are just protecting the children. That’s why Huntington Beach, California’s public library is having every single one of their children’s books– from board books to young adult– relocated out of the children’s section until they are audited for pornography. That’s why the public library in Donnelly, Idaho is “adults only” as of this last Monday. That’s why, apparently, it could soon be illegal to be a member of the American Librarian Association in Louisiana. To protect the children?

This is a lie, too. No child is safe in a classroom stripped of its books when someone with an unregulated AR-15 comes to school. Nevermind that pornography is easily sought on the internet, with just a couple key words, and that most children spend more time with their devices than they do in the public library. Ignore the very real accusations of grooming that come from various religious organizations.

Because this was never about the children.

That Black and LGBTQ books are so often the target of these bans should be no surprise. The framework for doing bodily harm against these groups is already in place. Police kill people from these groups with near impunity, and even citizens seem to have been deputized, as George Zimmerman’s exoneration proved, as the canonization of Kyle Rittenhouse on the far right has proved, and as the treatment of the man who murdered Jordan Neely proves.

And so it is a perilous time to be in our nation. I have been told we are witnessing the death rattle of a violent minority. But I believe that we are witnessing the rise of a uniquely American fascism. I hope I am wrong, but with all the recent decisions from the Supreme Court just this week, I doubt it.

If you wondered what major publishers are doing during this perilous time I have some bad news. Likely if you’ve heard of me before you are either facebook friends with my mother, or because of the story I’m about to tell you.

You’ve seen this logo before. Maybe you know Scholastic well from their book fairs or their book clubs. Probably your kids’ school has a direct relationship with them. They’re unique that way among big publishers because they go directly into schools. Their reputation among educators is powerful.

And a year ago, their Education Division offered me a deal. They wanted to license this book, LOVE IN THE LIBRARY. They wanted to repackage it, and bring it into all those schools they work with. Which is an incredible opportunity.

But only if I made an edit. My offer was contingent upon it. A whole paragraph about how what happened to my grandparents was not an isolated incident. How it’s part of a tradition.

But not only that: the word RACISM would be removed from the author’s note altogether.

I said no. Absolutely not. And I said so publicly.

I knew that saying no was passing on a strong opportunity to better poise this little book that I love and believe in so much for greater success. I wrote LOVE IN THE LIBRARY so it would be used in classrooms. Scholastic could make that happen for me. But the deal was too toxic to accept. Unwittingly or not, Scholastic was participating in the white supremacist tradition of using Asian stories as means to cast us as the model minority. Sure, Japanese Americans were interned back then, but look at them now! This drives a wedge between us and other marginalized groups. It divides us. And as the old adage goes, divided we fall.

Scholastic wanted me to occlude the truth of my grandparent’s story so that they could court the very same readers who have banned my book for being “Un-American.” They were more invested in reaching a small corner of the market than they were in preserving the most essential truth of their story. And this story is typical in traditional publishing. They are not unique in this tact.

We must be realistic. Capitalism will not save us. Our institutions are not proving up to the task of withstanding far right infiltration and destruction. Only our collective action opens the door of possibility for a better future. Only our commitment to truth and justice.

As the genocide in Palestine rages on, I wonder what offers have been made to Palestinian authors, if any offers have been made at all. There are a grand total of 4 traditionally published children’s books from major publishers about the Palestinian experience for the American market. By contrast, there are more than 30 books about Japanese American incarceration. We have a relative privilege. Our history of marginalization happened long enough ago that some white people will let us speak to it. That it took 80 years to reap this slim gain is a shame. However, it is our obligation to use that privilege all the same. Not just for our ancestors and families who deserve to have their experience honored, but for those whose stories bear tragic resemblance to our own, so that they can know that they are not alone.

That we stand with them.

If we had been presented with a wide array of Palestinian stories, told by Palestinian people, what would national opinion about the currently unfolding genocide look like? We don’t know, because those stories have been suppressed. And we, as the descendants and survivors of Minidoka know what it means to have our stories suppressed. To live in fear of our own voices. To feel obligated to sand down the sharp edges of our truths so we might even be invited to the table.

But remember:

Our grief humanizes us.

Our anger is galvanizing.

And our solidarity is more dangerous than any gun.

When we tell our stories with honesty and clarity, when we make the connections that desperately need to be made to other marginalized groups, we plant the seeds for change. It is our obligation, our responsibility, our duty as the keepers of these memories to ensure that they are not siloed away into sanitized capsules, unable to commingle with like narratives.

When I visited Minidoka last year it was the first time I had ever had a chance to visit. I was given a tour and videotaped as they walked me around and I tried my best to understand something so unfathomable. I came away freshly dedicated to telling my grandparents’ story.

I wondered what sites would some day be likewise preserved to ensure the commemoration of other brutal histories. If one day there would be a walking tour of the cages where immigrants on our southern border were held, punished for the dream of being American. If some day I would walk through the ruins of Khan Younis in Gaza, as a guide pointed out to me mass grave sites. But I wonder and I fret if we will ever be allowed to tell those stories at all as they deserve to be told— in 80 years, or ever.

We are all connected. Our liberation entwined. There is no Japanese American equality without Palestinian equality. There is no justice for the Holocaust without justice for the Nakba. No reparations for the descendants of the enslaved without land back for the first nations. There is no pride in genocide. Any injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.

The time for quiet distaste and disapproval has come and gone. To meditate on the truth of marginalization is to be called into action. Anything less than that only reveals a lack of true comprehension.

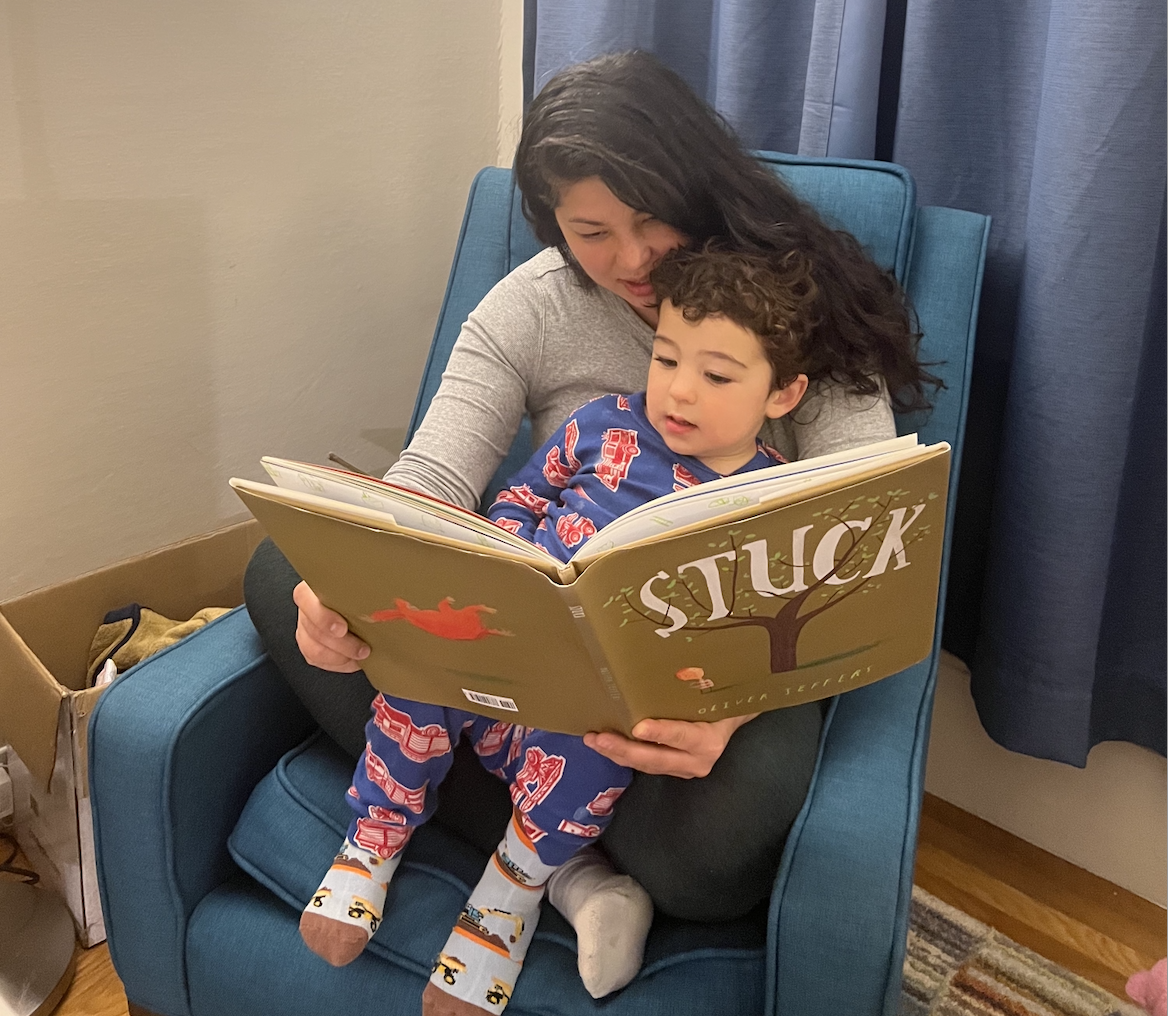

About a month ago, I took my son to an ice cream shop. He’s four. It was a big deal. He got a sundae. It was a perfect afternoon, the kind that just reinforces the great joy of being a parent, the endless delight of a child’s smile. I took a picture of him and like many insufferable millennials, I went to post that picture on instagram.

When I opened the app on my phone, I was immediately confronted with a video from Rafah— the city farthest to the south in the Gaza strip, where Palestinians were ordered to go by the Israeli military— the video was of a man, frantic, running through debris and flames with the body of a decapitated child. I looked away. I had to. But I have spent every day since October in the same state of numb horror that I think a lot of us are perpetually in, mourning for a child whose name I did not know, who was still my child all the same. A child who deserved everything my son has. To wear a silly hat, and to have a sweet with someone who loves them for exactly who they are.

All children deserve this. As James Baldwin said: “The children are always ours, all across the globe, every single one. And I am beginning to think that those who do not understand this are incapable of morality.”